Why an emergency fund matters

An emergency fund gives you time and options when life throws an unexpected expense or you lose income. Without one, people commonly rely on credit cards, high‑interest loans, or liquidating long‑term investments—moves that can damage credit scores and long‑term wealth. Federal Reserve and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau research show many U.S. households are vulnerable to income shocks; a dedicated emergency fund reduces that risk (see federalreserve.gov and consumerfinance.gov).

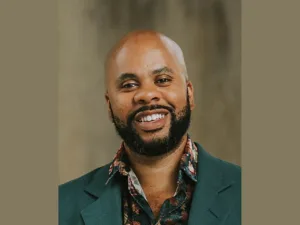

In my practice working with clients over 15 years, I’ve seen two consistent patterns: the households that kept even a modest emergency fund avoided panic-driven decisions, and those without one often paid significantly more over time to solve short-term problems.

How to calculate the right target for you

Follow this simple, repeatable process:

- Define your essential monthly expenses. Include only costs you must pay to keep the household running: rent or mortgage, utilities, groceries, transportation, insurance, minimum debt payments, and any essential childcare or medical costs.

- Add together the monthly totals to get your essential monthly expense amount.

- Multiply that number by a target number of months based on your risk profile (guidance below).

Target guidance (use your judgment):

- 3 months — starter target for dual‑income households with stable work and access to credit lines.

- 3–6 months — standard recommendation for most households.

- 6–12 months — prudent for freelancers, gig workers, single‑income households, or anyone in industries with layoffs or seasonal pay.

- 12+ months — useful for small‑business owners, people planning a major career transition, or those with chronic health expenses.

Example: If your essential monthly total is $3,000, then:

- 3 months = $9,000

- 6 months = $18,000

- 12 months = $36,000

Where to keep your emergency fund: balancing liquidity, safety, and yield

The two priorities are liquidity (can you access funds quickly?) and capital preservation (can you avoid loss?). Because emergency money is risk capital, invest it conservatively.

Recommended places to park an emergency fund:

-

High‑yield savings accounts (online banks). These offer immediate access and materially better interest than legacy brick‑and‑mortar savings. Make sure accounts are FDIC‑insured (up to $250,000 per depositor, per institution) (fdic.gov).

-

Money market deposit accounts. Similar to savings accounts with good liquidity and FDIC protection.

-

Short‑term Treasury bills (T‑bills). Bought via TreasuryDirect or a broker, T‑bills are backed by the U.S. government and can be highly liquid if sold on the secondary market. They may offer higher yields at times than bank accounts.

-

Short CD ladder (90–365 days). A CD ladder can improve yield while providing periodic liquidity. Avoid long‑term CDs that impose steep early‑withdrawal penalties.

Accounts and assets to avoid for primary emergency savings:

- Long‑term CDs or investments that charge penalties for early withdrawal.

- Stocks or mutual funds, which can fall in value exactly when you need cash.

- I Bonds are an excellent inflation hedge but have a mandatory 12‑month holding period and a penalty if redeemed within five years, so they’re not ideal for immediate emergencies.

In my client work I typically recommend a layered approach: keep a true “day‑to‑day” emergency balance (1–2 months’ essentials) in a very liquid HYSA or money market account, and the remainder of the emergency target in higher‑yield, still liquid instruments like a laddered series of short CDs or T‑bills.

Practical steps to build the fund

- Start small: open a separate savings account and aim for a $1,000 starter cushion. Psychology matters—seeing progress sustains savings behavior.

- Automate transfers: set up automatic transfers timed with payday so saving is frictionless. Treat the transfer like a fixed monthly bill.

- Cut nonessential spending temporarily: reallocate one‑time windfalls, tax refunds, or bonuses to the fund.

- Replenish immediately after use: if you withdraw for a true emergency, set a repayment schedule.

- Review annually: as your expenses change, update the target amount.

Automation tip: for variable or seasonal income, see our guide on adaptive budgeting for gig workers and how to stress‑test your plan (internal links below).

What to do if you can’t reach the ideal target right away

You don’t need to hit the full target before you’re protected. Use a step approach:

- Phase 1: Save a $1,000 starter fund.

- Phase 2: Reach one month of essentials.

- Phase 3: Reach three months; treat this as a meaningful short‑term goal.

- Phase 4: Progress toward six months and beyond.

At every stage, keep liquidity and safety in mind. Even a small fund significantly lowers the chance you’ll use expensive credit.

Common mistakes and how to avoid them

- Commingling emergency savings with spending accounts. Open a separate account and label it clearly.

- Using credit cards as your primary backup. High interest increases long‑term costs.

- Investing emergency money in volatile assets. Market drops can lock in losses when you need cash.

- Letting the fund grow unreplenished after a withdrawal. Make a plan to replace any amounts used.

Special situations and tailored guidance

-

Freelancers & contract workers: Aim for at least six months and ideally 9–12 months because income is variable. Also build a slow, automated habit of moving income into a dedicated savings account each time a client pays — see our post on adaptive budgeting for gig economy workers (https://finhelp.io/glossary/adaptive-budgeting-for-gig-economy-workers/).

-

Parents or caregivers: Include childcare and predictable medical costs in your essentials calculation and consider a larger cushion for single‑parent households.

-

Dual‑income households: You may safely aim for a smaller starter cushion if both incomes are stable and replaceable quickly, but aim for three months as a minimum.

-

Job transitions: If you plan to leave a job to pursue training or entrepreneurship, size your fund to cover the full planned transition period plus a contingency.

How to integrate an emergency fund with your broader financial plan

An emergency fund is the foundation. After you establish the emergency reserve, balance progress between paying down high‑interest debt and saving for retirement. If you’re unsure how to prioritize, a neutral rule is: build a starter emergency fund, then pay down high‑interest debt, then resume building the emergency fund while contributing to retirement accounts.

Also, test your budget under stress. Our guide on stress‑testing your budget helps you estimate the impact of sudden income loss and choose an appropriate emergency target (https://finhelp.io/glossary/stress-testing-your-budget-for-sudden-income-shocks/).

Quick decision checklist

- Do I have a separate account for emergencies? If no, open one today.

- Do I know my essential monthly expenses? If no, create a one‑page list and total it.

- Can I automate a regular transfer? If no, set up automation with even a small initial amount.

Professional disclaimer

This article is educational and does not constitute personalized financial advice. Your situation may require different targets or products. Consult a qualified financial planner or tax professional before making decisions that affect your long‑term finances.

Authoritative sources & further reading

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau: saving tips and tools (https://www.consumerfinance.gov)

- FDIC: deposit insurance FAQs (https://www.fdic.gov)

- Federal Reserve: economic research and household finance data (https://www.federalreserve.gov)

Internal resources on FinHelp:

- Adaptive budgeting for gig economy workers: https://finhelp.io/glossary/adaptive-budgeting-for-gig-economy-workers/

- Stress‑testing your budget for sudden income shocks: https://finhelp.io/glossary/stress-testing-your-budget-for-sudden-income-shocks/

- How to automate budget adjustments after a raise: https://finhelp.io/glossary/how-to-automate-budget-adjustments-after-a-raise/

By treating an emergency fund as a nonnegotiable part of your monthly plan, you buy time, avoid expensive credit, and preserve long‑term financial goals. Start where you are, automate progress, and protect that balance specifically for true emergencies.